A look at demographic development.

This essay was originally written as part of an application to a United Europe / Europaeum workshop on ‘The EU and the Western Balkans’. The question was specified by the organisers and was: “Is the EU/EU membership a solution for the Balkans? How could both benefit from this?”. Due to the limited length, it is very far from comprehensive or deep in its analysis, but expresses some initial thoughts.

The question ‚Is the EU a solution for the Balkans?‘ pre-supposes that there is a problem the Balkans, specifically the Western Balkan (WB) countries are facing as a collective. And indeed, they do currently share many political challenges as they are in a state of emerging democracy with a shared background in communism/socialism which is discussed in public on a day-to-day basis. However, there is a problem just as fundamental and much less discussed which the Balkan countries share that is slowly, invisibly, eroding them: demographic decline. Unlike political, cultural or economic changes, demographic trends can be forecast into the future reliably and more long-term and the forecast prospects for the Balkans are dire. The United Nations forecast that by the year 2100 the demographic powers of fertility, mortality and migration will have led to population decreases of 30 to 60 per cent of the current population in the Western Balkan countries. However, demographic developments are not inevitable. They are impacted by external circumstances such as current domestic and EU policies as well as potential future EU membership of the respective country. In the following, I will outline how the current relationship to the EU affects demographics on the Western Balkan, how EU membership would impact it and how both the EU and the Western Balkan countries could benefit from their relationship in demographic terms if shaped well.

To examine how the EU currently affects the demographics on the WB, three separate short analyses by the three factors affecting a population’s size mortality, fertility and migration will be conducted. Firstly, in terms of decreasing mortality, i.e. increasing life expectancy on the WB, the proximity to the EU, has, if anything, not led to the worse, but it is more likely that economic investments, infrastructure support in the medical field, the possibility to receive medical treatment in the more developed EU countries and peace-keeping efforts have contributed to a clear increase of life expectancy since 1990 in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

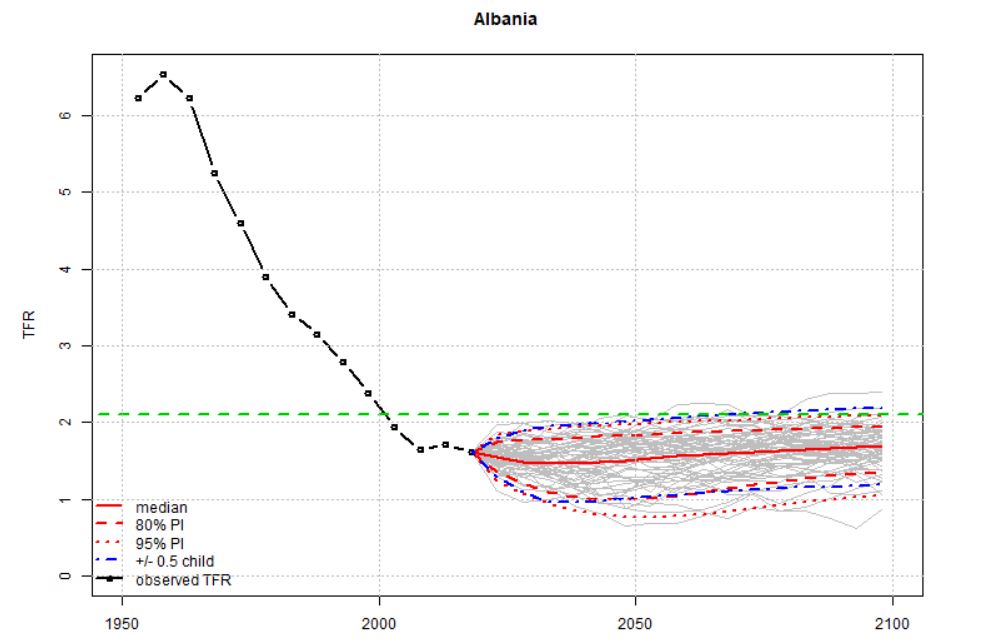

Fertility, just like mortality, has also started a trend of convergence with the levels of neighbouring countries. However, this is rather a disadvantage. While fertility levels in 1990 ranged from 2 to 3.4 children per woman, today they are between 1.3 and 1.7. This development seems to imitate the fertility trend of other South European countries of the total fertility rate (TFR) dropping to drastically low levels and stabilizing at around 1.3 to 1.5 children per woman. For an especially drastic example, see the graph of Albania’s fertility rate below where the fertility rate dropped from 6.5 in 1958 to 3.0 in 1990 to 1.6 in 2019. It is unclear which factors lead to this development precisely and how the relationship to the EU played into it but as the WB countries copied education, family and social welfare policies of the EU countries, in particular those which nowadays demonstrate severely low fertility rates, it is probable that there is a link. Although the WB countries currently still have a high share of youngsters, this low fertility will soon lead to challenges such as lack of labour supply and generational re-distributional power.

Copyright 2019 United Nations, DESA, Population Division.*

Lastly, along with the freedom of the individual in the 1990s came a loss for society: mass emigration. From the moment of opening, streams of migrants flowed to the EU, directed by everchanging asylum and immigration policies more than geographical proximity. This brought economic relief to those left behind and encouraged cultural change due to the remit of much new information, but it also caused a dip in population sizes which, to date, has continued its downward trend in all six WB countries over the last 30 years. On the one hand, this could be seen as a positive thing as labour markets burdened with too little employment and too many workers were relieved slightly, but on the other hand in the longer term this out-migration of mainly the younger generations has led and will lead to a decimation of the respective populations. The EU’s power in this situation lies in shaping immigration in such a way that it will not only be useful to itself, but also to these neighbouring countries by encouraging a true exchange of skills instead of a one-way flow, by creating easily comprehensible and stable visa policies which will enable successful migration instead of creating a mass of vulnerable, homeless peoples.

How, though, would EU membership affect this situation? Firstly, life expectancy, along with economic development would most likely increase just a bit further although an upper limit of current EU levels will soon be reached and increase will decelerate. Fertility levels are most likely to converge with those of lowest-fertility EU states more quickly, leading to an acceleration of the thinning out of the lower tiers of the population pyramids in the WB. And migration? This is where the true key to either the decimation or the success of the WB states’ populations lies. Either, and this situation cannot be taken too seriously and should be considered gravely by policy makers, facilitated movement to the EU will increase to such an extent, at a time when out-migration had just slowed down a bit after 30 years of exodus, that even the expected economic benefit over time of EU accession would do little to soften the blow of a population of less than half of that in the late 1980s in almost all the Western Balkan countries. Or, and this is the hope, both the WB countries and the EU states would pour resources into a good management of the transition and accession process, aiming to create employment before, during and after accession on the WB with FDIs, infrastructure processes and improved labour market policies. This way, labour migration would be slowed down in the short term. However, this would most likely be at the expense of the dire labour market needs in the West, thirsty for easily available young and skilled labour. How could the current EU states benefit from such a well-managed decision, though? In the mid and long term, there would be human and financial resources in the Western Balkan for education, for demographic recovery, and then for a meaningful and sustainable exchange of labour and other resources with the EU countries and migration of young people at much less drastic levels while ensuring political and economic stability and a slow, but steady cultural stabilization after the throes of transition in the Balkans.

*Licensed under Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0 IGO. United Nations, DESA, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019. http://population.un.org/wpp

Explanation: These charts are from the Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling of total fertility that has been carried out with fertility estimates. Please note that only a small selection of the probabilistic trajectories of total fertility is displayed (gray lines) for illustration. The median projection is the solid bold red line, and the 80% and 95% projection intervals are displayed as dashed and dotted red lines respectively. At the country level, the high-low fertility variants correspond to +/- 0.5 child around the median trajectory displayed as blue dashed lines. The replacement-level of 2.1 children per woman is plotted as green horizontal dashed line only for reference.